- Home

- T. Chris Martindale

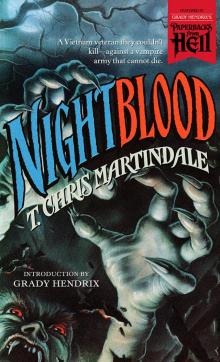

Nightblood Page 4

Nightblood Read online

Page 4

Not that there was much of a threat of that happening. He couldn’t remember a major crime around Isherwood in the last seven years, not since he’d put on the uniform and gun. Armed robbery? Well, little Ethan Stooly took five bucks out of Mrs. Moore’s register once. Assault? The occasional drunken brawl, a fight at the playground. Murder? Now that was a laugh. Isherwood hadn’t seen a murder or close to it for as long as he or anyone else could remember. Just the Danner story, he thought with a chuckle, and that morning’s Herald had said that it was all bunk, just a local legend after all.

Murder. Now that was wishful thinking. If only they’d have one now and then. Nothing big, mind you.

He made a sweep of the downtown area, especially Morty’s Pub, where a few of the locals sometimes got rowdy and ended up wrestling and puking on each other in the parking lot. This time it was empty. Must be a slow night. He went across the street and reached the IGA just about closing time and stuck around until all of the cashiers had made it to their cars and waved him on. Then he went across the lot to the Sunoco station which had closed an hour earlier, and pulled up in front to check the doors and buy a can of Mountain Dew.

There was a van sitting to one side, off-white with pitted fenders and a rash of rust on the lower panels. So, Mr. Stiles had taken his advice after all, he thought. Then he realized that this was a short-bed and the handyman’s had been a maxi. He looked around the rest of the lot but there were no other Dodges present.

He hadn’t seen Stiles all day, not since they talked on the street earlier that morning. Last he’d seen, the “handyman” was headed toward the diner for a cup of coffee and was still there well past noon. Bean had spied him twice through the window. He was keeping Billie preoccupied, that was for sure. She was fawning over him and rolling her eyes and laughing and damn near crawling over the counter onto his lap, for Christ’s sake. It wasn’t that Bean was jealous or anything—he’d only taken Billie out a few times in all the years he’d known her and hell, he was tied up with Susie these days. She just shouldn’t have been acting that way toward a stranger, that’s all.

Stiles must have had that kind of effect on people, he figured. Instant likability. He was not an unpleasant-looking man, he supposed, and he was soft-spoken and friendly, the kind of person you take to right off like a long-lost fishing buddy or high-school chum. But Bean refused to buy it. He had trained himself to look beyond a person’s veneer, to probe beneath the skin so to speak. There was something hidden behind that young man’s lean, bearded face, behind those intense eyes. There were secrets there. And that bothered him.

Bean may have had Stiles pegged in his own mind, but he still hadn’t decided what to do about him. On the one hand he was a nice enough guy and had threatened no one and done nothing wrong that he knew of. And until he did so, he had every right to be where he was. On the other hand, he was a question mark, a random element that gave the deputy a case of the mental itchies, and he would’ve slept a lot easier with Stiles on his way. And yet, Bean was curious. Part of him wanted to sit back and wait, and watch, and see what kind of trouble Stiles might want to stir up.

Murder. That was wishful thinking. . . .

One last pass by Moore’s Diner. The lights were still on—on weekends they were open till almost 2 a.m. for the late-night crowd—but Stiles’s van was no longer across the street and hadn’t been since late afternoon. He knew it was gone, but not where, and that was like an itch he couldn’t scratch. He sort of hoped Stiles might come back, just so he could keep tabs on him. Billie was working a double shift herself tonight, and that was incentive enough. But no such luck. He headed for the Tri-Lakes Inn, the only motel in town. But the parking lot was still empty. No van there either.

Maybe he’s gone, he figured with a mixture of relief and disappointment. Maybe I scared him off this morning.

Nah. Not very likely.

He glanced at his watch and started the last leg of the patrol.

Sykes Road split from Croglin Way before it reached Isherwood, directly across from the “Welcome” sign, and cut to the west. It rolled through farm and field for the first mile and forest for the second. But it was the next stretch that was popular. Especially at night.

They called it the Tunnel. It was almost a mile of poplar and dogwood and oak and elm that crept right to the edge of the ill-maintained pavement and reached out over it with groping limbs. Those limbs in turn formed a canopy so dense that even in losing their leaves they still held the light at bay and kept the roadway in a perpetual gloom. Daylight there was spooky enough; riding into the Tunnel was like entering some nether realm, haunted and surreal. Children were fond of riding their bikes out there. It was a test, actually, to see who could stay there the longest before their imaginations went too wild. Before the wind became a man’s voice, crying for help, before the looming trees took on human form and began to uproot themselves to give chase. Bicycles left the Tunnel much faster than they entered, but their pale riders would conquer their fears long before they reached town and already begin planning their next trip out there.

Bean mounted the next rise and the Tunnel came into view, at least what he could see of it. In the dark it was amorphous, an amoebic void blacker than the night around it. It swallowed Sykes Road whole and refused to spit it out. As he drove toward its gaping maw his mind conjured images of a great cave or, worse yet, a monstrous serpent, and then he was past the jaws and into its throat, leaving the starlight behind. It was in that instant before his eyes had time to adjust to the gloom, when his headlights were the only lights in the whole world, that he felt a communal twang of panic. Afraid of the dark. He could never be completely free of it. No one could.

This was the real Tunnel, he observed, the after-dark Tunnel. Pitch black, or as close as you’d want to get. Quieter. Scarier. More fun. At night it was a carnival funhouse for the bigger kids, the ones with cars and a girl to impress. The softening asphalt had become badly rutted after years of nocturnal traffic, and the tire-worn grass just off the road and between the trees had completely given up and refused to grow. There were other places in Isherwood to hang out like the IGA parking lot and Dante’s “new” pizza place and the video arcade, but as long as the weather held out the Tunnel was the place. It was a warped kind of tunnel of love, a make-out lane where Vincent Price or Rod Serling would feel at home amid the twisted trunks and heart-carved bark. Once the motor was turned off, the silence would close in, and wind would sift through the trees like a whispery voice, and the arthritic limbs overhead would sway and send the dimmest of shadows to dance on the ground around them, and that was where the stories always began. The escaped psychopath with a hook for a hand. The vanishing hitchhiker in the mud-spattered prom dress. The rapist glimpsed hunkered in the backseat of a woman’s car. Each would tell a story more horrific than the last until the girl jumped into her young man’s arms, or vice versa. And the rest . . .

He could pick out the individual cars now as he cruised slowly by: most had pulled far enough off the road so as to be obscured by weeds and trees, but a few were in plain view. There was a glimpse of bobbing heads and bare legs here and there, and one couple was clinched on the hood of a Mustang, seemingly oblivious to the nip in the air. But most were hidden behind well-steamed windows.

Bean was always amazed when he patrolled the Tunnel at just how loose kids were today. Not that he was a prude. He’d had his share of sexual escapades over the years and was more than happy to discuss them in detail with anyone who cared to listen. But these were high-school kids. Hell, when he was in high school, copping a feel was a week’s worth of bragging. Nowadays . . .

There was nothing here, at least nothing he should be concerned with. No brawls with jealous boyfriends, no out-of-town punks looking to cause trouble, no unwelcome advances from overamorous suitors. It was a comparatively quiet night. How boring. Might as well cut it short and call it a night.

Norm

ally he would’ve U-turned in the middle of Sykes Road and gone back to the office to tie in the lines and go home, and he was never more anxious to do so than tonight. He had a lot of apologizing to do, and a lot of arguing and probably a fair amount of begging as well. But something kept the squad car pointed straight ahead, out of the Tunnel and on into the night. Maybe it was the old curiosity. He saw the Danner place often enough: they patrolled the Tunnel and the rest of Sykes regularly even though it was outside city limits, mostly as a favor to the county boys. But he usually had the day shift, and it was different then. Certainly different than he remembered it.

Like most kids from Isherwood, he had gone out to the Danner place once, at night, to see if the stories were true. He hadn’t seen anything—to his knowledge no one ever did—but there had been a certain feeling.

He shrugged off the recollection, dismissing it as the product of a childish imagination. We’ll see, he told himself. We’ll see.

The road past the Tunnel was traveled less frequently. Indeed, this entire area was less developed, less populated, and the Danner legend played an important role in that. The land out there was tainted, some said, and no matter how much evidence you showed to the contrary you could not convince them otherwise. But, ironically, the same superstition which had stagnated suburban growth on this side of town appeared to be the prime reason for future development. Local lack of interest in the land had driven prices way down, and it was those prices that were attracting attention from Bedford and elsewhere. Out-of-towners didn’t give a damn about local horror stories, not when the bottom line was a good per-acre value. It wouldn’t be long, he reckoned, till Sykes Road would be lined with driveways, the Tunnel would be no more, and the “spreading evil” of the Danner estate would be a housing division with two-car garages and cable TV. There was even talk of rezoning the town and pushing the boundaries out to encompass more. Our town is growing, the mayor and his cronies were fond of saying, a little overoptimistically, Bean thought. But most of the “residents” did live outside the present limits and perhaps it was time for a change.

The Danner land was an actual part of Isherwood. He wished he could be a mouse in the council chamber when that came on the agenda. There was sure to be fireworks.

The gloom and spookiness had lifted once he’d cleared the Tunnel and now it was just another chilly, star-flecked night. It was still decidedly unspooky when he rounded a bend and came to the big iron gate of the Danner place.

There was a car parked in front.

It was a Ford Torino, red with a white stripe along the side like the car Starsky and Hutch used to drive. He had a good idea whose it was—how many like that could there be around town—but to be cautious he flicked his lights to high-beam and eased in behind the Ford and just waited.

Two figures moved inside, silhouetted by his headlights, and then the driver’s door swung open and a stocky figure stepped out brandishing a Louisville Slugger and squinting against the brightness. Bean sighed and hit the dimmer switch and let Ted Cooper’s eyes adjust so he could see the bubble-gum machines on top of the cruiser. Recognition set in gradually; the young man broke into a relieved grin and relaxed his grip on the bat and came sauntering back to the cruiser. He leaned in the window. “Hiya, Charlie,” Ted said in his deep, older-than-seventeen tone. “What’s the poop?”

“What’re you ’uns up to, Teddy?” Bean asked in his usual soft drawl. He reserved his policeman’s clipped severity for speeders and drunks and general assholes.

Cooper shrugged. “Just looking. Doreen hadn’t been out here before. I told her you can’t see anything from the road, but—” He just shook his head, the old “you-know-women” gesture.

“Well, lookee here,” Bean advised. “I’d appreciate it if you and puss would go back to the Tunnel or on home or someplace else. That place is pretty run-down. I want to make sure no one goes running around in there and getting themselves bunged up.”

Ted looked hurt. “We weren’t gonna go inside, Charlie.”

“I know you weren’t, Teddy, but I’d appreciate it if you move on anyway. Okay?”

Cooper thought a moment and then bobbed his head compliantly. “Whatever you say, Charlie. Doreen was starting to get scared anyway.” He strolled back to his car, dragging his bat and yelling, “How about some fishing ’fore it gets too bad” over his shoulder. The deputy waved a reply as the young man gunned the Ford and swung it out onto Sykes Road and back toward town.

Charlie Bean sat there for a moment and stared at the gate. He turned off the lights and the motor and just sat, letting the silence of night flood in around him. He didn’t know what he expected to happen, but whatever it was, it didn’t.

He stepped out of the car and walked over to the gate, retracing steps he took as a boy. The gate had looked so big then, so imposing, as if it held back all the demons of hell. But now . . . well, now it was just an antique, corroded by time and the pollution-tainted elements. He peered through the bars at the shadowy woods beyond as Papaw’s words came back to him and Pa’s voice after that, repeating the same litany as they sat around the fireplace. Don’t go near it, Charlie. The land is astink with evil. It’s in the soil, in the roots, and the groundwater. He planted it there, he did, Sebastian Danner. And it’s his ghost that’ll reap its unholy harvest for all of eternity.

But there was no harvest evident through the gate, except for the milkweed and poison ivy that had grown wild and uninhibited through the years. It was just woods. A little gloomy, but that’s all.

He looked at the bars, then at his own moist palms, remembering smaller hands that had shook at the prospect of touching them. This time he didn’t hesitate. He reached out and grabbed the bars. And gasped. But because they were cold, nothing more. There was no squirming evil inherent in the metal, no malignant charge of energy to course through his palms and along his spine.

Nothing.

He walked back to the car, satisfied that he had finally outgrown childhood fears and superstitions, and yet somehow disappointed. He had always given the stories a sort of reverence, no matter how much he scoffed, because they were tradition. His mother and father had believed, and their parents before them. Now, standing there in front of the gate and feeling not even an inkling of fear, he realized he’d just proven them all fools.

He climbed into the cruiser and drove back toward town, wishing he hadn’t even gone out there in the first place.

As soon as the deputy’s car was out of sight, a pair of headlights flashed to life back in the underbrush across the road from the Danner gate.

Chapter Three

The T-Bird eased out of hiding and parked in front of the gate where the Torino had sat minutes before. Tommy Whitten cut the engine and sent a stream of tobacco juice through the gap in his teeth. “Jeez, thought they’d never leave,” he sneered, tipping his dad’s flask to his lips. He leaned across the other two teens sandwiched into the front seat and peered out the passenger side. “So that’s the Danner place, huh? I don’t know, Miller. Looks pretty spooky to me.”

The other two nodded in agreement. One of them, Doug Baugh, sat bolt upright and craned his neck to look around the car. “What was that?” he whispered, waggling the cigarette cemented to his rubbery lower lip. “You guys heard it too, didn’t you?”

“I did,” whined “Fat Larry” Hovi, trembling a little too fearfully. His acting wasn’t up to par and he couldn’t keep the giggle out of his voice. “Sounds like something back in the trees . . . coming closer. . . .” The giggle began to win out.

In the backseat, Bart Miller turned to look at his younger brother Del, and the boy replied with a grin of reassurance. “You weenies can cut it out now,” Bart reported to the front seat. “I already told you, he just doesn’t scare easy.”

Del, age eleven, beamed in the glow of his brother’s praise, but his own estimation of his courage was considerably less. H

e was acting, pure and simple: he only wished he was as stout-hearted as Bart bragged. Sure, he’d seen all the splatter flicks, the Living Dead movies. Sure he’d accumulated a collection of Fangoria despite Mom’s protests, and devoured every blood-soaked page without a tremor of uneasiness or disgust. But there was a difference between a strong stomach and a strong backbone.

He looked out the window at the gate. It was large and looming, bigger than when they first drove up, a tremendous thing of wrought iron and rusted hinges. The lock must have failed with age; it was now secured at the center bars by a log chain and Master Lock from the hardware store. That made it even worse, Del thought. It reinforced the warning that the gate itself implied: DO NOT ENTER. IN GOD’S NAME, DO NOT ENTER.

Stars pierced the night, he noticed, everywhere but beyond the gate. The trees there were creating the shade, he knew, but the effect was still the same. A land of complete darkness, of ever-night, a realm of evil, the gate to . . .

Don’t enter. In God’s name . . .

He lowered his eyes. Don’t think about it. You’re going and that’s it.

He wouldn’t do this for anyone else, not for a million bucks, not even for the fifty they were betting. Hell, who gave a shit what these stupid grits from Seymour thought of Isherwood and them? But a dare was a dare. Besides, he and Bart would show ’em that “Woodies” weren’t scared of no ghost stories, and they’d win some pocket money to boot.

Nightblood

Nightblood